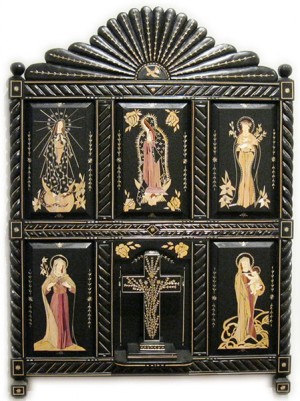

The stunning straw appliqué work of artists such as Jean Anaya Moya continues a centuries-old European tradition that was introduced to New Mexico and flourished in the late-17th through the mid-19th centuries. Often called “poor man’s gold,” the technique was developed to mimic marquetry, a form of decorating wooden items, typically with inlaid wood, ivory, shell, or gold.

The stunning straw appliqué work of artists such as Jean Anaya Moya continues a centuries-old European tradition that was introduced to New Mexico and flourished in the late-17th through the mid-19th centuries. Often called “poor man’s gold,” the technique was developed to mimic marquetry, a form of decorating wooden items, typically with inlaid wood, ivory, shell, or gold.

Although it was considered a lost art form at the end of the 19th century, it perpetuated at the Pueblo of Santa Ana and made a dramatic resurgence through support from the WPA and the 1956 revival of the Spanish Market in Santa Fe. Jean Anaya Moya’s continuation of this form of art begins with many traditional materials but then combines modern materials such as acrylic paint and commercial glues and varnish. She states that her designs are “traditional Hispanic religious images with a contemporary twist… it is extremely important to create art that people can relate to.” She continues, saying that “some change is always good as long as we never forget how we evolved.”

Luis Tapia, a Santa Fe native, began carving santos in 1970 and “looks for the nourishment of blending tradition with contemporary culture so that the tradition may continue to grow and flourish.” He has made a place for himself in the mainstream contemporary art world; although his bold colors and updated themes may break from strict tradition, it is with no intention to disrespect or satirize traditional forms. The popularity of Tapia’s work is a testament to the artist’s belief that it is his responsibility to create new forms rather than copy the old, stating, “I am the tradition.” Tapia received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1980 and has shown his work in such notable venues as the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, the Corcoran Gallery, and the Museum of International Folk Art, and he is represented in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution, the National Museum of American Art, and the Los Angeles Craft and Folk Art Museum.

Husband and wife team Eulogio and Zoraida Ortega began making santos later in life, in 1975, after Eulogio had already served in the army and worked as a school principal and Zoraida retired from teaching. Eulogio had originally studied art education and had received a master’s degree in painting and sculpture, so woodcarving came naturally and he found the history of the craft fascinating. His first piece was a bulto of San Rafael that he decided to carve after he read about a statue by the great santero José Rafael Aragon that had been stolen from a chapel in Chimayo. Although the sculpture was recovered before Ortega could complete a replacement, the artist was already committed to pursuing the craft. His wife Zoraida, an award-winning weaver, would become his collaborator and the painter of Eulogio’s carvings, as well as painting her own retablos.The couple’s work is nationally known and collected by both private individuals and museums and has been featured in many Southwestern art books and periodicals. Perhaps their best known and most revered work is the Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe Chapel, constructed by the couple as a testament of faith after Zoraida’s battle with cancer. The chapel, located in Velarde, NM, brings visitors from around the world for its beauty and for healing.

Renowned photographer Alex Harris is represented in collections of institutions such as the J. Paul Getty Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Metropolitan Museum and has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. The founder of the Center for Documentary Photography and Documentary Studies at Duke University spent six years from 1972 – 1978 living in and photographing villages in northern New Mexico, resulting in perhaps his best known work, Red White Blue and God Bless You, published in 1992. The image on display is from this series of 45 photographs and offers an intimate glimpse into the co-existence of secular and sacred culture in the lives of his adopted community.